Advanced production practices and performance: empirical evidence from Spanish plants

Author

Darkys Luján-García – (Universidad de Sevilla)

Pedro Garrido-Vega – (Universidad de Sevilla)

Bernabé Escobar-Pérez – (Universidad de Sevilla)

Abstract

This paper presents an empirical study that analyses the effect of applying three Advanced Production Practices (APPs) (Total Quality Management-TQM, Just in Time-JIT, and Total Productive Maintenance-TPM) on business performance measured with financial and non-financial (or operational) indicators. The study was conducted on a sample of Spanish companies in the automotive components, electronics and machinery sectors that took part in the 3rd Round of the High Performance Manufacturing (HPM) Project. The results of an analysis using Partial Least Squares (PLS) show that only two of the nine implementation indicators for the APPs being analyzed (process emphasis in TQM, and JIT delivery by suppliers) are positively related with non-financial performance. No significant relationship was found with financial performance, or between operating and financial performance. However, it should be borne in mind that the small size of the sample used in this study only enables strong relationships to be detected; a larger sample would be required to detect moderate or weak relationships.

Keywords

- Advanced production practices

- Financial performance

- Operating or non-financial performance

1. Introduction

The need to improve their competitiveness has led companies to embark upon initiatives in the production area to enhance operations performance by optimizing the use of resources and reducing costs. These initiatives and actions have been perfected over time until they became what today are known as Advanced Production Practices (APPs). These then became widespread internationally. They represent broad concepts linked to productive activities, and in most cases, there is no consensus on their definition or their potentiality (Cua et al., 2006).

The most important APPs that have been studied and applied from the beginning of this revolution in Production Management include Total Quality Management (TQM), Just in Time (JIT) and Total Productive Maintenance (TPM), which some authors include among the pillars of World Class Manufacturing (Schonberger, 1986). Whether applied separately or, preferably, in an integrated way, these APPs have a positive impact on several areas of the company with valuable outcomes in a number of aspects on the plant level, such as: better customer satisfaction, reductions in the production cycle and a fall in delivery times, to mention but a few (Flynn et al., 1995; Abdel-Maksoud et al., 2005; Cua et al., 2006).

The degree to which these APPs are applied is measured using various “indicators” and/or “scales” which have become standardized and perfected over time (Flynn et al., 1995 and Cua et al., 2001, 2006). The relationship between APPs application and performance measured with operational and non-financial measures (NFI) has been addressed in depth in the specialized literature (Abdel-Maksoud et al., 2005). However, financial indicators (FI) have been less used in the context of APPs and the findings of the studies that have used them are not entirely conclusive (Fullerton and Wempe, 2009). The two types of indicator need to be considered jointly to measure performance if advances are to be made in the evaluation of APP implementation.

In keeping with the above, this paper conducts an empirical analysis of the effect of the three above-mentioned APPs on both operational, or non-financial, performance and financial performance, as well as of the relationship between the two types of performance.

The following section examines the antecedents to the research that supports the hypotheses, prior studies related to APP application and their relationship with both operational and financial performance indicators. The third section presents the methodology followed to conduct the study. Subsequently, the research findings are set out, and then discussed in Section five. Finally, the conclusions drawn from this study are presented along with future lines of research.

2. Antecedents and hypotheses

This section reviews prior research on indicators used for the application of the three APPs considered and their relationship with financial and non-financial performance.

The decision was taken to formulate the hypotheses from a positive point-of-view, as, in economic terms, it is logical to suppose that companies invest in APPs, such as TQM, JIT/LM and TPM, amongst others, in the pursuit of improvements in the efficacy and efficiency of their processes and, therefore, of their performance, irrespective of how it is measured. In this way, they will at least recover the investments that they have made.

2.1. Total Quality Management (TQM)

TQM is a holistic focus production practice designed to improve effectiveness and operating efficiency. It involves the entire organization and focuses on complying with and surpassing customer expectations (Dahlgaard et al., 2007; Kumar et al., 2011). Numerous studies can be found in the literature that analyze the implementation of this APP and its effect on both operating/non-financial and financial performance obtained by companies (e.g., Flynn et al., 1995; Agus et al., 2000; Agus, 2005; Cagwin and Barker, 2006; Demirbag et al., 2006; Yeung et al., 2006).

Among the main indicators, constructs and scales that have been used to measure the implementation of this APP are: continuous improvement and learning, customer focus, customer involvement, customer satisfaction, feedback, company-wide focus, preventive process control, process emphasis, supplier alliances, supplier quality improvement, top management leadership for quality, TQM–customer link, problem- solving and supplier quality level teams.

Logically, no study uses all of these indicators, but rather a group of them depending on the purpose of the research. Amongst the most used are customer involvement, supplier quality improvement and process emphasis, and these are the indicators that will be used in this study. It will be noted that these three indicators focus on the three major phases of the productive process: suppliers, the process per se and customers, thus providing an overview of TQM.

2.1.1. Customer Involvement (CI)

Customer Involvement, or Customer Focus, as some authors prefer to call it (Ahmad and Schroeder, 2002; Sila and Ebrahimpour, 2005), is one of the most used indicators in the context of TQM implementation (e.g., Powell, 1995; Curkovic et al., 2000; Cua et al., 2001, 2006). Some studies have proven that customer involvement affects both operational/non-financial -flexibility, cost, delivery, etc. (Cua et al., 2001, 2006) and financial investment performance, market share, etc. (Curkovic et al., 2000) performance positively. There are also some studies, such as Sila and Ebrahimpour (2005), that find no relationship between Customer Focus and the business results, measured using non-financial indicators (productivity, cycle times and number of errors or defects, among others) and financial indicators (profit and ROA, among others).

The following hypotheses were proposed in line with earlier studies:

H1a: There is a positive relationship between CI and operational or non-financial performance.

H1b: There is a positive relationship between CI and financial performance.

2.1.2. Supplier Quality Improvement (SQI)

This is another important indicator in the context of TQM implementation (Flynn et al., 1995; Cua et al., 2001, 2006; Kaynak, 2003; Sila and Ebrahimpour, 2005). Abusa and Gibson (2013) have proven that it is positively related to performance indicators, such as the defect rate, increased sales and increased profit. However, Sila and Ebrahimpour (2005) again found no significant relationship between this indicator and the business results.

The following hypotheses can therefore be formulated:

H2a: There is a positive relationship between SQI and operational or non-financial performance.

H2b: There is a positive relationship between SQI and financial performance.

2.1.3. Process Emphasis (PE)

The third indicator used in the context of TQM is process management emphasis (Saraph et al., 1989; Claver et al., 2003; Cua et al., 2001, 2006; Prajogo and Sohal, 2006; Abusa and Gibson, 2013). Proper process management improves non-financial indicators, such as the product defect rate (Saraph et al., 1989; Claver et al., 2003; Abusa and Gibson, 2013) and delivery time (Cua et al., 2001). However, Samson and Terziovski (1999) do not find that this indicator has a positive effect on the organization’s performance measured through customer satisfaction, productivity, percentage of defective products, quality costs, etc. In light of the above, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H3a: There is a positive relationship between PE and operational or non-financial performance.

H3b: There is a positive relationship between PE and financial performance.

2.2. Just In Time (JIT)/Lean Manufacturing (LM)

Just in time (JIT) was first implemented in the Toyota Motor Company and then spread throughout the West in the nineteen-eighties (Singh and Singh, 2013). JIT philosophy is basically aimed at eliminating wastage, understood as anything and everything that adds cost to the product but no value (Schonberger, 1982). Specifically the main sources of wastage, as defined in JIT, include excess inventory, scrap and reprocessing (Brox and Fader, 2002).

Some authors currently consider JIT as the core of a wider APP, Lean Manufacturing (Bortolotti et al., 2013; Klingenberg et al., 2013). Much research has been carried out into applying JIT/LM and their impact on operational/non-financial performance and financial performance (Boyd,2001; Callen et al., 2003; Inman et al.,2011).

In a literature review, Mackelprang and Nair (2010) found a total of ten indicators that have been commonly used to measure JIT: reduced lead time, small lot size, JIT delivery by suppliers, keeping to a daily schedule, preventive maintenance, equipment layout, the Kanban system, the JIT-customer link, the pull system and the repetitive nature of the master program.

The three most classic indicators from those above, used in over 90% of the studies analyzed, will be used in this research: the Kanban system, equipment layout and JIT delivery by suppliers.

2.2.1. Just in Time Delivery by Suppliers (JTDS)

There are a great number of studies (Forza, 1996; Callen et al., 2000; Shah and Ward, 2003; Das and Jayaram, 2003; Ketokivi and Schroeder, 2004; Swink et al., 2005; Li et al., 2005; Narasimhan et al., 2006; Avittathur and Swamidass, 2007; Matsui, 2007; Dal Pont et al., 2008) that have used this indicator to measure JIT implementation. These papers have examined the effect of JTDS on five non-financial (operational) performance indicators indiscriminately: inventory level, cycle time, deliveries, quality, cost and flexibility. Basing themselves on these earlier studies, Mackelprang and Nair (2010) proved that JTDS has a medium impact on the above-mentioned performance indicators. Phan & Matsui (2010) found that the relationship between JIT production practices and plant performance was contingent on the national context and infrastructure practices in quality and workforce management. In particular, JTDS was correlated with some of the five performance indicators (cost, on-time delivery, volume flexibility, inventory turnover and cycle time) but not all in all countries.

However, no study has been found that verifies the relationship with the company’s financial results. In spite of this, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H4a: There is a positive relationship between JTDS and operational or non-financial performance.

H4b: There is a positive relationship between JTDS and financial performance.

2.2.2. Kanban System

Fifteen studies in all have been found in the bibliography that use this indicator in the context of JIT (Sakakibara et al., 1997; Lieberman and Demeeter, 1999; Fullerton and McWatters, 2001; Fullerton and McWatters, 2002; Fullerton et al., 2003; Callen et al., 2003; Christiansen et al., 2003; Ahmad et al.,2004; Cua et al.,2001, 2006; Ward and Zhou, 2006; Matsui, 2007; Bayo-Moriones et al., 2008; Inman et al., 2011; Danese et al., 2012). One of the main findings is that Kanban has a significant effect on advanced manufacturing technologies (AMT), basic quality tools and the management of vertical relationships (Bayo-Moriones et al., 2008). Meanwhile, Danese et al. (2012) proved that implementing JIT production (using the Kanban system as one of the indicators to measure its implementation) is directly related with enhanced delivery performance.

Fullerton et al. (2003) found increasing marginal returns to long-term JIT investment for JIT practices such as Kanban and JIT purchasing in a time-series model. However, they found an insignificant association in a full cross-sectional model. This suggests that the benefits of these JIT practices are realized only over time and that they are negatively associated with profit in some stages of JIT adoption.

In line with the above, the following hypotheses are formulated:

H5a: There is a positive relationship between the Kanban system and operational or non-financial performance.

H5b: There is a positive relationship between the Kanban system and financial performance.

2.2.3. Equipment Layout (EL)

Cua et al. (2001) and Mackelprang and Nair (2010) have used this indicator to measure the effects of JIT implementation. Cua et al. (2001) use it along with four further items to measure JIT implementation. They conclude from the study that EL is not significantly related to non-financial/operational performance (measured through cost efficiency, conformance quality, on-time deliveries and volume flexibility) either when the implementation of the APP is analyzed on its own, or when contingency factors are taken into account. Meanwhile, more recently Mackelprang and Nair (2010) conducted a meta-analysis of the relationship between JIT and operating performance (measured through cycle time, deliveries, quality, cost and flexibility) and found eight articles published in journals in the areas of operations management, management, marketing and logistics from 1992 to 2008 that use EL to evaluate the implementation of JIT. Based on these studies, the finding is that EL has a medium impact on operating/non-financial performance, although it is not always significant.

No research study was found that examines the relationship of this indicator with financial performance, therefore the following hypotheses are proposed:

H6a: There is a positive relationship between EL and operating or non-financial performance.

H6b: There is a positive relationship between EL and financial performance.

2.3. Total Productive Maintenance (TPM)

Total productive maintenance (TPM) was originally developed in Japan and is based on a preventive system that involves all levels of the plant, from the Plant General Manager to the shop floor worker. Its application has proved to be a success, as it results in greater productivity and an increase in the efficiency of production equipment (Keung, 2003).

Some of the classic indicators used to assess TPM implementation are autonomous maintenance, preventive maintenance and maintenance support.

2.3.1. Autonomous Maintenance (AM)

McKone et al. (2001), Ahuja and Khamba (2008) and Lazim et al. (2013) have used this indicator to evaluate TPM implementation on the plant level. Ahuja and Khamba (2008) demonstrated that TPM implementation has fostered autonomous maintenance. This is reflected in improvements in some aspects, such as the elimination of waste, improvements in the reliability of manufacturing processes and cost reductions. Meanwhile, Lazim et al. (2013) state that autonomous maintenance-related activities result in large reductions in manufacturing costs (including production costs, labor, and general materials and unit costs).

The following hypotheses are proposed on the basis of the above:

H7a: There is a positive relationship between AM and operational or non-financial performance.

H7b: There is a positive relationship between AM and financial performance.

2.3.2. Preventive Maintenance (PM)

This is another major indicator to be taken into account when implementing TPM (Nakazato, 1994; Abdallah, 2013). Nakazato (1994), specifically, evaluates it through daily maintenance and periodic maintenance. Swanson (2001) demonstrated that proactive/preventive maintenance was positively related with improvements to product quality, improvements in equipment availability, and reduction in production costs. Konecny and Thun (2011) found that TPM implementation was positively related with non-financial performance (quality, cost, time and flexibility), but that the Preventive Maintenance indicator was the weakest of the three indicators used to evaluate TPM.

On the basis of the above the following hypotheses are proposed:

H8a: There is a positive relationship between PM and operational or non-financial performance.

H8b: There is a positive relationship between PM and financial performance.

2.3.3. Maintenance Support (MS)

Another of the indicators that is usually used to measure TPM is the support or aid given to the maintenance function (Abdallah, 2013). This indicator refers to issues such as the setting of maintenance standards, the management of replacement parts and systems for information on equipment breakdowns. Although it is an important indicator in the context of TPM, no studies have been found that evaluate its effect on financial and non-financial performance. Given the foregoing, the following hypotheses are proposed for testing:

H9a: There is a positive relationship between MS and operational or non-financial performance.

H9b: There is a positive relationship between MS and financial performance.

2.4. The relationship between the non-financial operational indicators and the financial indicators

According to Baines and Langfield-Smith (2003), most research states that a great deal of confidence is placed on the information provided by financial and non-financial indicators to evaluate both past and prospective activities. However, the relationship between these two types of indicator is very ambiguous and there is no precise knowledge of what the real interaction between them is.

To be specific, some research studies have been found that examine the relationship between the two types of indicator on the basis of the application of some APPs. Ittner and Larcker (1995) found that a greater use of non-financial indicators is linked to improvements in financial performance both when quality programs are formalized and in environments where they are not. Perera et al. (1997) concluded that there is an increase in the use of non-financial indicators in companies that adopt advanced manufacturing practices. Nonetheless, they found no link with financial performance measured as an increase in the sales rate, net profit/revenue and return on assets. Meanwhile, Callen et al. (2000) found that non-financial indicators were not related to profit either at plants that implemented JIT or those that did not.

Other studies state that there is a positive relationship between these two types of indicator. Such is the case of Durden et al. (1999), Baines and Langfield-Smith (2003) and Said et al. (2003), who state that a greater use of non-financial information is linked with improvements to financial indicators. More recent studies, such as Fullerton and Wempe (2009) and Hofer et al. (2013), test for the existence of a mediating or moderating effect of non-financial indicators between the implementation of APPs and the financial results.

Despite the lack of consensus found in the prior literature regarding the relationship between operational and financial indicators, it is reasonable to suppose that if improvements are made to the former -a reduction in the number of defective products or a shorter response time, for example- this would have a knock-on effect on income and, more especially, on costs, and consequently, also on the economic-financial result and, evidently, the company’s performance. Thus, the last hypothesis to be tested is as follows:

H10: There is a positive relationship between operational or non-financial performance and financial performance.

3. Methodology

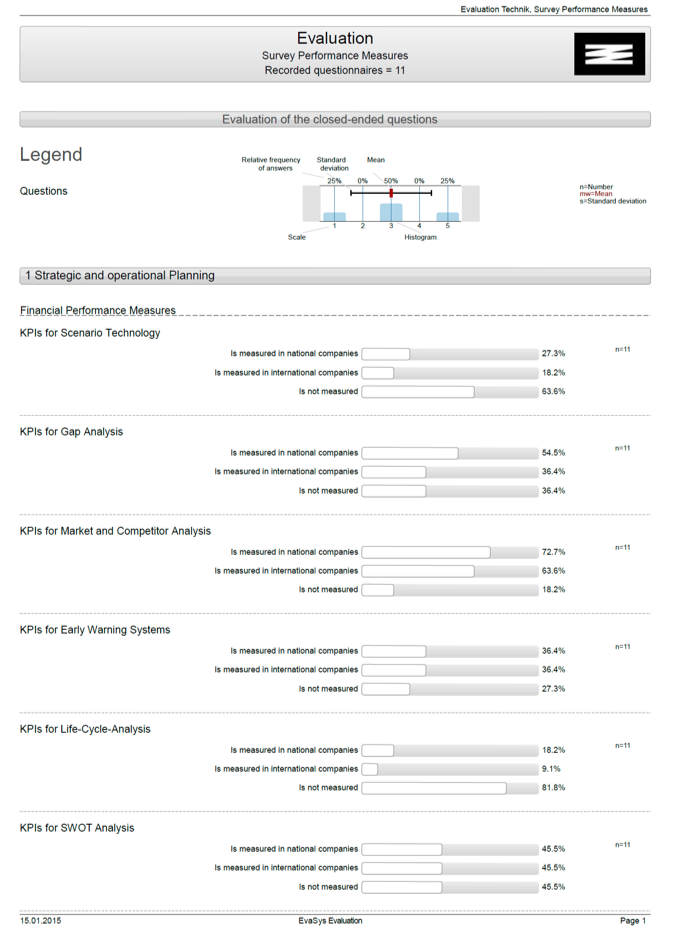

Data from the International High Performance Manufacturing (HPM) Project will be used in this empirical study. The objective of this project is to use an extensive survey to analyze the factors that contribute to the success of high performance manufacturers (Schroeder and Flynn, 2001; Hallgren and Olhager, 2009). To be precise, there are 12 questionnaires that contain information on all plant levels and are administered to 21 informants in the study (10 senior management, 6 supervisors and 5 production workers). These questionnaires contain hundreds of questions, most of which are scored using perceptual scales.

Information for this article has been taken from the database relating to indicators of the implementation of the aforementioned APPs and to operational (non-financial) performance corresponding to the Spanish plants that took part in the 3rd Round. In this project, a stratified design was used to randomly select an approximately equal number of plants (with at least 100 workers) across three industrial sectors in each country. Specifically, the sample used in this study is made up of a total of 20 plants in the auto components, electronics and machinery sectors. The sample size qualifies it as a borderline sample (i.e., one where the size is just adequate to satisfy a statistical power analysis) that requires care on the part of the researchers when choosing the tools for the analyses and when making interpretations (Avittathur and Swamidass, 2007).

Two of the most commonly used indicators in previous research were used to evaluate operational/non-financial (NFI) performance: delivery time and flexibility to change the product mix (e.g., Sim, 2001; Ahmad et al., 2004).

The financial data used in the study were taken from the SABI (the Iberian Balance Sheet Analysis System) commercial database, as the HPM 3rd Round database does not contain sufficient financial data. The financial indicator taken for the study was return on sales (ROS) for the 2007 tax year. This performance indicator is very important for Fullerton and Wempe (2009) as it is (1) widely accepted as a measure of financial performance; (2) has proven to be a determinant of improved return on assets (ROA) for companies that adopt JIT (Kinney and Wempe, 2002); and (3) it eliminates some of the confusion that inventory reductions cause for ROA. The study will also be conducted with Cash Flow Margin or EBITDA Margin (EBITDA/Net Sales) to see whether the results that are obtained are similar.

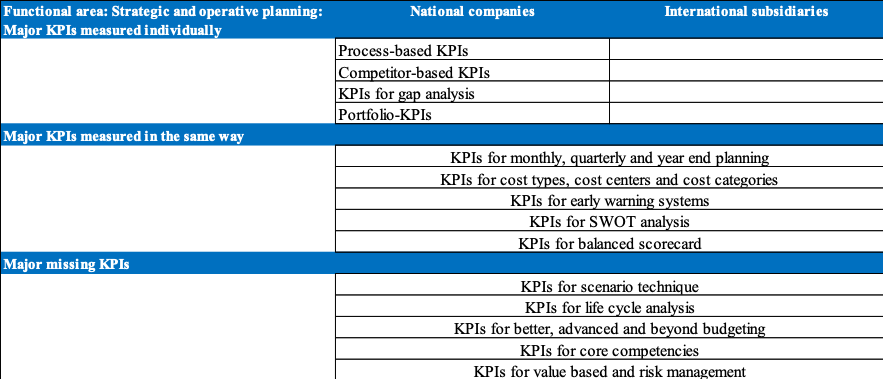

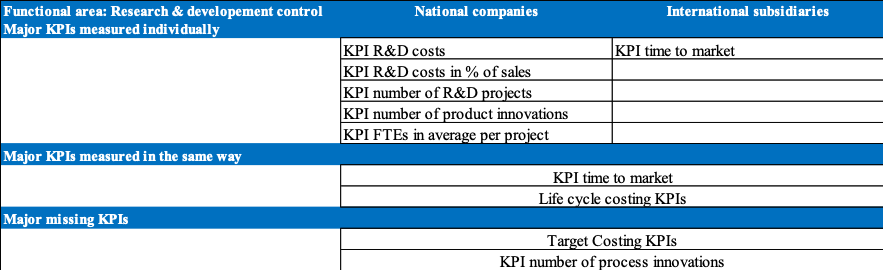

In a similar way to Fullerton and Wempe (2009), this study aims to analyze a model that relates the APP indicators with the NFI and with ROS (Table 1).

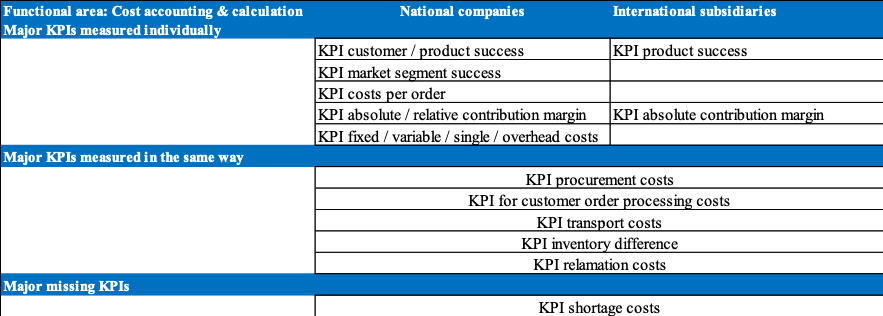

Advanced Production Practices (APPs) | TQM Customer involvement (CI) Supplier quality improvement(SQI) Process emphasis(PE) | JIT Kanban system(Kanban) Just-in-Time Delivery by Suppliers (JTDS) Equipment layout (EL) | |

TPM Autonomous maintenance (AM) Preventive maintenance (PM) Maintenance support (MS) | |||

Performance indicators | Non-financial indicators (NFI) On time delivery Flexibility to change product mix Flexibility to change volume | Financial indicator

Return on Sales (ROS) | |

Table 1: Implementation indicators used for each APP and performance indicators.

Annex 1 provides details of all the items included in the questionnaires that make up the indicators of the three APPs (TQM, JIT/LM and TPM) and the respective loads obtained in factor analysis. As can be seen, all the items present suitable loads (over 0.4 are considered important according to Hair et al., 1999) on their respective indicators or constructs.

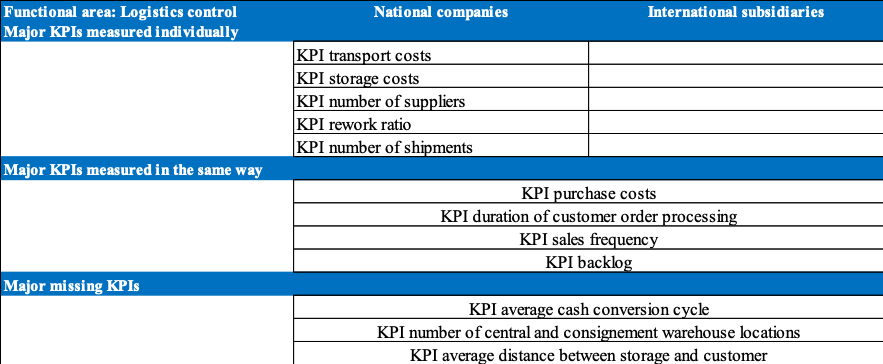

The APPs will be analyzed separately due to the small size of the sample. There are therefore three research models to be tested (see Figure 1).

Figure 1a: TQM model

Figure 1b: JIT model

Figure 1c: TPM model

Figure 1: Relationship models by APP.

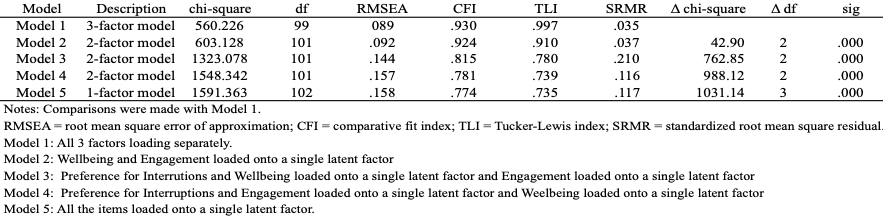

Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) was used to evaluate the models and test the hypotheses using Smart PLS statistical software. PLS-SEM procedures have recently gained great acceptance in studies on business management and the economy (Hair et al., 2011). There are already some examples specifically linked to operations management, such as Hartmann and De Grahl (2012) and Kim et al. (2013) that address topics linked to the outsourcing of logistics services, and supply chain management, respectively. Meanwhile, PLS is a technique that enables very small samples to be worked with, as is the case of this research, and it places few prior statistical assumptions on the data.

The use of this technique involves two phases (Barclay et al., 1995). Phase 1 refers to the evaluation of the measurement model for the validity and reliability of the constructs. In phase 2, the structural model is evaluated and the proposed hypotheses are tested (Henseler et al., 2009).

4. Results

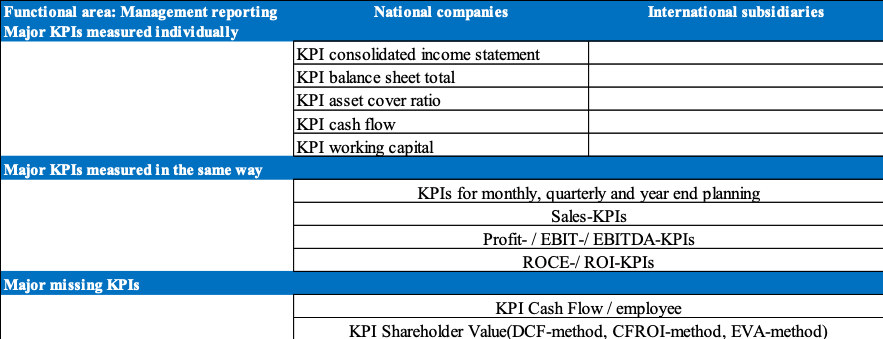

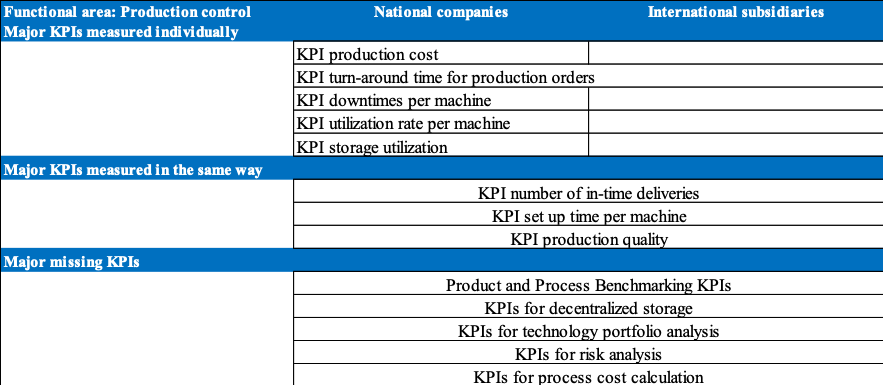

4.1. Phase 1: Evaluation of measurement model (outer model)

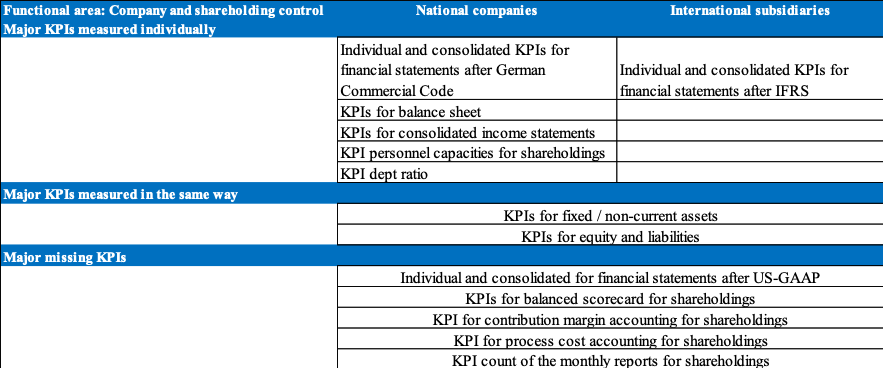

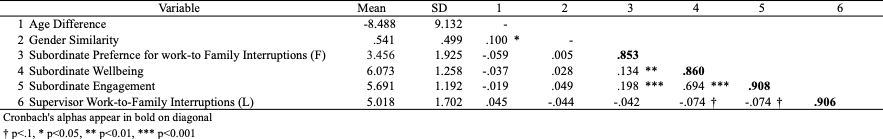

The main results of Phase 1 are given in Table 2, which shows the measurement model quality criteria for each of the models. Firstly, the composite reliability (CR) index was used for the reliability analysis. The score for this indicator must be greater than 0.7 for the construct to be reliable (Nunnally and Bernstein, 1994). The scores in the last column of Table 2 show that all the constructs possess a suitable level of reliability as they are all greater than 0.7. Secondly, the convergent validity is evaluated. This is shown by average variance extracted (AVE) (Fornell and Larcker, 1981). The AVE scores must be over 0.50 for the indicator to be valid (Henseler et al., 2009; Hair et al., 2011). As the Table shows, all the constructs present convergent validity as all the AVE scores exceed 0.519. Thirdly, the degree to which any given construct differs from the other constructs was also tested, i.e., discriminant validity. Following the Fornell-Lacker (1981) criterion, the square root of the AVE values should be greater than the latent variable correlations (not shown in Table 2). This criterion is met for all the constructs.

TOTAL QUALITY MANAGEMENT (TQM) | |||

CR | AVE | Discriminant Validity? | |

CI | 0.917 | 0.735 | YES |

PE | 0.846 | 0.650 | YES |

SQI | 0.891 | 0.672 | YES |

NFI | 0.831 | 0.621 | YES |

JUST IN TIME (JIT) | |||

CR | AVE | Discriminant Validity? | |

JTDS | 0.803 | 0.580 | YES |

EL | 0.879 | 0.646 | YES |

Kanban | 0.933 | 0.822 | YES |

NFI | 0.817 | 0.602 | YES |

TOTAL PRODUCTIVE MAINTENANCE (TPM) | |||

CR | AVE | Discriminant Validity? | |

AM | 0.918 | 0.789 | YES |

MS | 0.804 | 0.579 | YES |

PM | 0.812 | 0.519 | YES |

NFI | 0.826 | 0.614 | YES |

Table 2: Measurement model quality criteria.

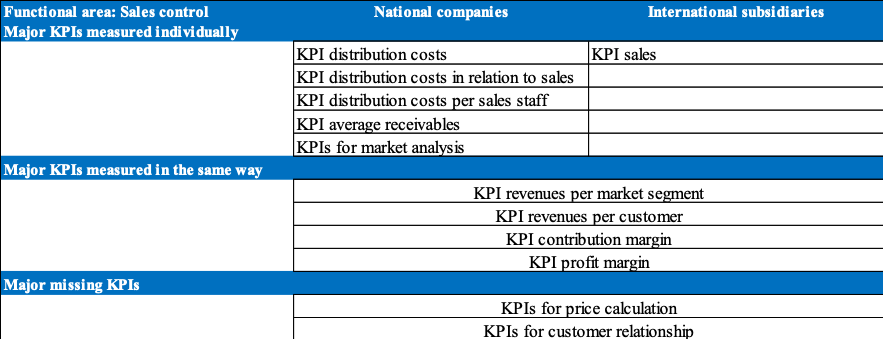

4.2. Phase 2: Evaluation of the structural model (inner model)

This section gives the results of hypothesis testing once the measurement model used has been satisfactorily evaluated. The first criterion for evaluating a PLS-SEM is to evaluate the determination coefficient (R2) of the endogenous constructs (Hair et al., 2011). The value of R2 represents a measure of the model’s capacity for prediction (Henseler et al., 2009). Falk and Miller (1992) recommend that R2 should be at least greater than 0.10. The R2 values exceeded the permitted maximum; despite this, high values were not recorded for the two endogenous variables (ROS and NFI) in any of the models under study (see Table 3).

A non-parametric re-sampling technique (bootstrapping) is used (with 2000 samples) to examine the statistical significance of the estimations obtained. Table 3 shows the path coefficients and the t-student statistical test that enable the hypotheses to be tested. The path coefficients must be positive and the t-student scores must be greater than 1.646 (value corresponding to a one-tailed, asymmetrical test of significance α=0.05) for the hypotheses to be supported and for the relationships to be significant.

TOTAL QUALITY MANAGEMENT (TQM) | ||||

Relationships | Path coefficients | t –student | R2 | HYPOTHESIS SUPPORTED?* |

H1a-CI -> NFI | -0.431 | 1.123 | NO | |

H1b-CI ->ROS | 0.103 | 0.253 | NO | |

H2a-SQI -> NFI | -0.045 | 0.131 | NO | |

H2b-SQI -> ROS | -0.162 | 0.578 | NO | |

H3a-PE -> NFI | 0.566 | 2.089* | YES | |

H3b-PE -> ROS | -0.370 | 1.072 | NO | |

H10a- NFITQM -> ROSTQM | 0.362 | 0.910 | NO | |

Endogenous variables | NFITQM | 0.289 | ||

ROSTQM | 0.204 | |||

JUST IN TIME (JIT) | ||||

Relationships | Path coefficients | t –student | R2 | HYPOTHESIS SUPPORTED?* |

H4a-JTDS -> NFI | 0.697 | 2.153* | YES | |

H4b-JTDS -> ROS | 0.334 | 0.663 | NO | |

H5a-Kanban -> NFI | -0.104 | 0.406 | NO | |

H5b-Kanban -> ROS | -0.407 | 1.527 | NO | |

H6a-EL -> NFI | -0.061 | 0.191 | NO | |

H6b-EL -> ROS | 0.037 | 0.092 | NO | |

H10b-NFIJIT-> ROSJIT | 0.119 | 0.321 | NO | |

Endogenousvariables | NFIJIT | 0.389 | ||

ROSJIT | 0.234 | |||

TOTAL PRODUCTIVE MAINTENANCE (TPM) | ||||

Relationships | Path coefficients | t –student | R2 | HYPOTHESIS SUPPORTED?* |

H7a-AM -> NFI | 0.072 | 0.199 | NO | |

H7b-AM -> ROS | 0.492 | 1.317 | NO | |

H8a- PM -> NFI | 0.106 | 0.351 | NO | |

H8b-PM -> ROS | 0.141 | 0.369 | NO | |

H9a-MS -> NFI | 0.373 | 1.141 | NO | |

H9b-MS -> ROS | -0.480 | 1.423 | NO | |

H10c-NFITPM -> ROSTPM | 0.321 | 0.984 | NO | |

Endogenousvariables | NFITPM | 0.229 | ||

ROSTPM | 0.438 | |||

*p < 0.05 (based ont (1999) = 1.6456, one-tailed test)

Table 3: Hypothesis testing.

5. Discussion

In general terms, the results of this study are in line with prior studies that find no clear relationship between the implementation of these APPs and performance, financial performance especially.

With respect to the a hypotheses that refer to operational or non-financial (NFI) indicators, only TQM dimension, Process Emphasis (PE) (H3a) and Just-in-Time Delivery by Suppliers (JTDS) (H4a) as a dimension of JIT, have been found to be significantly related to operational performance, whilst all the other indicators show non-significant relationships that are even negative on occasion. This result is partially in keeping with the findings of Sila and Ebrahimpour (2005) and Fullerton et al. (2003), to mention only two studies. However, Cua et al. (2006) found that the joint implementation of TQM, JIT and TPM (not examined in this study due to the sample size) is linked to higher levels of operational performance. We believe that the following circumstances should be taken into account for a better interpretation of these findings:

- The size of the sample is too small as we were only able to work with data from 20 Spanish plants. This does not allow for the necessary statistical power to detect effects of moderate or small size.

- As there is no consensus on the definition and scope of the APPs’ implementation indicators, the way in which their application has been measured might influence the results. Three indicators have been used per APP in this study, and these were chosen from those that were found to be the most used in a literature review. Nonetheless, other indicators or dimensions of APPs exist that might yield different findings.

- The fact that operational performance has been considered as a single dimension, as a single construct, could be obscuring other positive results that the application of APPs could have on the individual operational performance aspects considered (on-time delivery and flexibility to change the product mix) or on other aspects that have not been included (cost, speed, quality, etc.). A future analysis could examine the effect of the APPs on the various aspects of operational performance separately.

- The success of APP implementation depends above all on contingent factors (e.g., company size, number of employees, etc.) not considered in this research that impact on the success of their application.

With regard to the b hypotheses, which link the implementation indicators for each APP with financial performance as a dependent variable, the results are partially in line with Ittner and Larcker (1995) and Fullerton et al. (2003). No significant results were found between any of the APP implementation indicators and ROS, and some of the coefficients are even negative. Therefore, the results for ROS are even worse than for NFI as far as the hypotheses being supported is concerned. When interpreting these results it has to be borne in mind that APP application has been measured on the plant level, while the financial performance indicator is measured at the company level. This might be the reason why the results do not show the real relationship between the implementation indicators for each APP and financial performance, and it will therefore be important to distinguish between the two units of analysis in future studies. In addition, it should be taken into account that ROS, like any other measure of financial performance, is affected by many other company factors, which do not come under the direct responsibility of the Production Manager. This raises an issue that cannot be solved easily, as this circumstance affects any measure of financial performance. In fact, the models were recalculated using the EBITDA Margin and the results were very similar.

Finally, no relationship was found between NFI and ROS (H10a, b and c) in any of the models for the different APPs. As stated in Section 2, this is a relationship that has been less studied by the academic community. This result is in line with prior studies, such as Callen et al. (2000), although there are other studies, such as Fullerton and Wempe (2009) and Hofer et al. (2013) that have found a direct effect between non-financial performance and ROS. In this case, however, despite the results not being significant, the coefficients are positive in the three models analyzed.

6. Final considerations and future research

This paper presents an empirical study that analyses separately the effect of implementing three main APPs (TQM, JIT/LM and TPM) on performance. Three different models, one for each of the APPs, with first-order reflective constructs were tested. Each APP was measured using three related implementation indicators. As performance is a very broad and diverse concept, it has been measured in this study using both non-financial and financial indicators. Non-financial indicators are the indicators par excellence for analyzing APP performance, whilst the financial indicators add valuable information on the performance of the APPs from the financial/accounting perspective. The indicators complement each other and provide the required information about the performance obtained from the APPs. The study was conducted in 20 Spanish plants in the machinery, automotive components and electronics sectors.

Measuring the implementation of these broad APPs that are multi-dimensional and complex and of performance itself is difficult in both cases, as witnessed by the generalized lack of agreement in this respect. Although companies make enormous efforts and investments to implement APPs with the intention of improving their performance and competitiveness, the relationship between the two variables is still difficult to grasp, in spite of all the papers that have been published. This study makes an empirical contribution to our knowledge of this relationship, which is very important for companies and also arouses great interest in the scientific community.

The results of the study indicate that the application of the APPs was related, but to a limited extent, to non-financial performance, specifically Delivery by Suppliers for JIT, and Process Emphasis for TQM. However, no relationship was found with financial performance, in this case, ROS. In general terms the results are in line with a part of the extant literature. It is supposed that the operating indicators are those that are most directly related with the APPs. However, despite financial performance depending on many other factors, apart from these APPs, some significant relationship might have been anticipated. Nevertheless, as already stated in the section 5, these results could have been affected by the small sample size.

As future research, the intention is to reproduce this study, but with a larger sample and also including plants from other both developed and emerging countries. The number of indicators to be used could also be increased both to evaluate the effective implementation of the APPs and to measure financial and non-financial performance. Finally, although it is more difficult to analyze, perhaps it would be appropriate to bear in mind the time delay in financial results when improvement programs are applied, in this case, the implementation of APPs.

Acknowledgments

This research has been partly funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation, project DPI-2009-11148, and by the Junta de Andalucía project P08-SEJ-03841. The authors wish to acknowledge both Governments’ support.

References

Abdallah, A. B. (2013). The Influence of “Soft” and “Hard” Total Quality Management (TQM) Practices on Total Productive Maintenance (TPM) in Jordanian Manufacturing Companies. International Journal of Business and Management, 8(21), 1-13.

Abdel-Maksoud, A. B., Dugdale, D. and Robert, L. (2005). Non-financial performance measurement in manufacturing companies. The British Accounting Review, 37(3), 261-297.

Abusa, F. M. and Gibson, P. (2013). Experiences of TQM elements on organizational performance and future opportunities for a developing country. International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management, 30(9), 920-941.

Agus, A. (2005). The Structural Linkages between TQM, Product Quality Performance, and Business Performance: Preliminary Empirical Study in Electronics Companies. Singapore Management Review, 27(1), 87-105.

Agus, A., Krishnan, S.K. and Kadir, S.L. (2000). The structural impact of total quality management on financial performance relative to competitors through customer satisfaction: A study of Malaysian manufacturing companies. Total Quality Management, 11, 808-819.

Ahmad, A., Mehra, S. and Pletcher, M. (2004). The perceived impact of JIT implementation on firms’ financial/growth performance. Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management, 15(2), 118-130.

Ahmad, S. and Schroeder, R. G. (2002). The importance of recruitment and selection process for sustainability of total quality management. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 19(5), 540-550.

Ahuja, I.P.S. and Khamba, J.S. (2008). Assessment of contributions of successful TPM initiatives towards competitive manufacturing. Journal of Quality in Maintenance Engineering, 14(4), 356-374.

Avittathur, B. and Swamidass, P. (2007). Matching plant flexibility and supplier flexibility: lessons from small suppliers of U.S. manufacturing plants in India. Journal of Operations Management, 25(3), 717–735.

Baines, A. and Langfield-Smith, K. (2003). Antecedents to management accounting change: a structural equation approach. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 28, 675–698.

Balakrishnan, R., Linsmeier, T.J. and Venkatalachan, M. (1996). Financial Benefits from JIT Adoption: Effects of Customer Concentration and Cost Structure. Accounting Review, 71(2), 183-205.

Barclay, D., Higgins, C. and Thompson, R. (1995). The Partial Least Squares (PLS) approach to causal modeling: personal computer adoption and use as an illustration. Technology Studies, 2(2), 285-309.

Bayo-Moriones, A., Bello-Pintado, A. and Merino-Diaz-De-Cerio, J. (2008). The role of organizational context and Infrastructure practices in JIT implementation. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 28(11), 1042-1066.

Bortolotti, T., Danese, P. and Romano, P. (2013). Assessing the impact of just-in-time on operational performance at varying degrees of repetitiveness. International Journal of Production Research, 51(5), 1117–1130.

Boyd, D.T. (2001). Corporate adoption of JIT: The effect of time and implementation on selected performance measures. Southern Business Review, 26(2), 20-26.

Brox, J.A. and Fader, C. (2002). The set of just-in-time management strategies: an assessment of their impact on plant-level productivity and input-factor substitutability using variable cost function estimates. International Journal of Production Research, 49(12), 2705–2720.

Cagwin, D. and Barker, K.J. (2006). Activity-based costing, total quality management and business process reengineering: their separate and concurrent association with improvement in financial performance. Academy of Accounting and Financial Studies Journal, 10(1), 49-77.

Callen, J.L., Fader, C. and Krinsky, I. (2000). Just-in-time: A cross-sectional plant analysis. International Journal of Production Economics, 63(3), 277–301.

Callen, J.L., Morel, M. and Fader, C. (2003). The profitability-risk tradeoff of just-in-time manufacturing technologies. Managerial and Decision Economics, 24(5), 393-402.

Christiansen, T., Berry, W. L., Bruun, P. and Ward, P. (2003). A mapping of competitive priorities, manufacturing practices, and operational performance in groups of Danish manufacturing companies. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 23(10), 1163-1182.

Claver, E., Tari, J.J. and Molina, J.F. (2003). Critical factors and results of quality management: an empirical study. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 14(1), 91-118.

Cua, K.O., McKone, K.E. and Schroeder, R.G. (2001). Relationships between implementation of TQM, JIT, and TPM and manufacturing performance. Journal of Operations Management, 19(6), 675-694.

Cua, K.O., McKone-Sweet, K. E. and Schroeder, R. G. (2006). Improving Performance through an Integrated Manufacturing Program. The Quality Management Journal, 13(3), 45-60.

Curkovic, S., Vickery, S. and Droge, C. (2000). Quality-related action programs: Their impact on quality performance and firm performance. Decision Sciences, 31(4), 885-905.

Dahlgaard, J., Kristensen, K. and Kanji, G.K. (2007). Fundamentals of Total Quality Management. Routledge: New York.

Dal Pont, G., Furlan, A. and Vinelli, A. (2008). Interrelationships among lean bundles and their effects on operational performance. Operations Management Research, 1, 150–158.

Danese, P., Romano, P. and Bortolotti, T. (2012). JIT production, JIT supply and performance: investigating the moderating effects. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 112(3), 441-465.

Das, A. and Jayaram, J. (2003). Relative importance of contingency variables for advanced manufacturing technology. International Journal of Production Research, 41(18), 4429–4452.

Demirbag, M., Tatoglu, E., Tekinkus, M. and Zaim, S. (2006). An analysis of the relationship between TQM implementation and organizational performance. Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management, 17(6), 829-847.

Durden, C. H., Hassel, L. G. and Upton, D. R. (1999). Cost accounting and performance measurement in a just-in-time production environment. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 16(1), 111-125.

Falk, R.F. and Millner, N.B. (1992). A primer for soft modeling. The University Akron: Ohio.

Flynn, B.B., Sakakibara, S. and Schroeder, R.G. (1995). Relationship between JIT and TQM: Practices and performance. Academy of Management Journal, 38(5), 1325-1360.

Fornell, C. and Larcker, D.F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18, 39-50.

Forza, C. (1996). Achieving superior operating performance from integrated pipeline management: an empirical study. International Journal of Physical Distribution and Logistics Management, 26(9), 36–63.

Fullerton, R. R. and Wempe, W.F. (2009). Lean manufacturing, non-financial performance measures and financial performance. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 29(3), 214-240.

Fullerton, R.R. and McWatters, C.S. (2001). The production performance benefits from JIT implementation. Journal of Operations Management, 19(1), 81-96.

Fullerton, R.R. and McWatters, C.S. (2002). The role of performance measures and incentive systems in relation to the degree of JIT implementation. Accounting Organization and Society, 27(8), 711-735.

Fullerton, R.R., McWatters, C.S. and Fawson, C. (2003). An examination of the relationships between JIT and financial performance. Journal of Operations Management, 21(4), 383-404.

Green, F.B., Amenkhienan, F. and Johnson, G. (1991). Performance Measures and JIT. Management Accounting, 72(8), 50-53.

Hair, J.F., Anderson, R.E., Tatham, R.L., and Black, W.C. (1999). AnálisisMultivariante (5th edition). Prentice Hall: Madrid.

Hair, J.F., Ringle, C.M. and Sarstedt, M. (2011). PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. Journal or Marketing Theory and Practice, 19(2), 139–151.

Hallgren, M. and Olhager, J. (2009). Lean and agile manufacturing: external and internal drivers and performance outcomes. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 29(10), 976-999.

Hartmann, E. and De Grahl, A. (2012). Logistics outsourcing interfaces: the role of customer partnering behavior. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 42(6), 526-543.

Henseler, J., Ringle, C.M. and Sinkovics, R.R. (2009). The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. Advances in International Marketing, 20, 277-320.

Hofer, C., Eroglu, C. and Hofer, A.R. (2012). The effect of lean production on financial performance: The mediating role of inventory leanness. International Journal of Production Economics, 138(2), 242-253.

Inman, R. A., Sale, R. S., Green, K. W. and Whitten, D. (2011). Agile manufacturing: Relation to JIT, operational performance and firm performance. Journal of Operations Management, 29(4), 343-355.

Ittner, C.D. and Larcker, D.F. (1995). Total quality management and the choice of information and reward systems. Journal of Accounting Research, 33(3), 1-34.

Kaynak, H. (2003). The relationship between total quality management practices and their effects on firm performance. Journal of Operations Management, 21, 405–435.

Ketokivi, M. and Schroeder, R.G. (2004). Manufacturing practices, strategic fit and performance: a routine-based view. International Journal of Operations and Production Management, 24(2), 171–191.

Keung, H. S. (2003). The Implementation and Evaluation of Total Productive Maintenance (TPM)—An Action Case Study in a Hong Kong Manufacturing Company. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology, 2(2), 224-228.

Kim, M., Suresh, N. C. and Kocabasoglu-Hillmer, C. (2013). An impact of manufacturing flexibility and technological dimensions of manufacturing strategy on improving supply chain responsiveness: Business environment perspective. International Journal of Production Research, 51(18), 5597-5611.

Kinney, M.R. and Wempe, W.F. (2002). Further evidence on the extent and origins of JIT’s profitability effects. The Accounting Review, 77(1), 203-225.

Klingenberg, B., Timberlake, R., Geurts, T.G. and Brown, R.J. (2013). The relationship of operational innovation and financial performance-A critical perspective. International Journal of Production Economics, 142(2), 317-323.

Konecny, P. A. and Thun, J. (2011). Do it separately or simultaneously-an empirical analysis of a conjoint implementation of TQM and TPM on plant performance. International Journal of Production Economics, 133(2), 496-.507.

Kumar, V., Batista, L. and Maull, R. (2011). The impact of operations performance on customer loyalty. Service Science, 3(2), 158-71.

Lazim, H. M. and Salleh, M. N. (2013). ChandrakantanSubramaniam, and SitiNorezam Othman, Total Productive Maintenance and Manufacturing Performance: Does Technical Complexity in the Production Process Matter?. International Journal of Trade, Economics and Finance, 4(6), 380-383.

Li, S., Rao, S.S., Ragu-Nathan, T.S. and Ragu-Nathan, B. (2005). Development and validation of a measurement instrument for studying supply chain management practices, Journal of Operations Management, 23(6), 618–641.

Lieberman, M. B. and Demeester, L. (1999). Inventory reduction and productivity growth: Linkages in the Japanese automotive industry. Management Science, 45(4), 466-485.

Mackelprang, A. W. and Nair, A. (2010). Relationship between just-in-time manufacturing practices and performance: A meta-analytic investigation. Journal of Operations Management, 28, 283–302.

Matsui, Y. (2007). An empirical analysis of just-in-time production in Japanese manufacturing companies. International Journal of Production Economics, 108 (1-2), 153-164.

McKone, K. E. A., Schroeder, R. G. B. and Cua, K. O. (2001). The impact of total productive maintenance practices on manufacturing performance. Journal of operations Management, 19, 39–58.

Nakazato, K. (1994). Autonomous Maintenance. In Suzuki, T. (Ed.), TPM in Process Industries. Productivity Press; Portland.

Narasimhan, R., Swink, M. and Kim, S.W. (2006). Disentangling leanness and agility: an empirical investigation. Journal of Operations Management, 24(5), 40–457.

Nunnally, J.C. and Bernstein, I.H. (1994). Psychometric Theory. McGraw-Hill: New York.

Perera, S., Harrison, G. and Poole, M. (1997). Customer-focused manufacturing strategy and the use of operations-based non-financial performance measures: A research note. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 22(6), 552-557.

Phan, C.A. and Matsui, Y. (2010). Comparative study on the relationship between just-in-time production practices and operational performance in manufacturing plants. Operations Management Research, 3(3-4), 184-198.

Powell, T.C. (1995). Total quality management as competitive advantage: A review and empirical study. Strategic Management Journal, 16(1), 15-37.

Prajogo, D.I. and Sohal, S. S. (2006). The relationship between organization strategy, total quality management (TQM), and organization performance––the mediating role of TQM. European Journal of Operational Research, 168, 35–50.

Roberts, N. Thatcher, J. B. and Grover, V. (2010). Advancing operations management theory using exploratory structural equation modeling techniques. International Journal of Production Research, 48(15), 4329-2353.

Said, A., Hassabelnaby, H.R. and Wier, B. (2003). An Empirical Investigation of the Performance Consequences of Nonfinancial Measures. Journal of Management Accounting Research, 15, 193-222.

Sakakibara, S., Flynn, B. and Schroeder, R. (1997). The impact of just-in-time manufacturing and its infrastructure on manufacturing performance. Management Science, 43(9), 1246-1257.

Samson, D. and Terziovski, M. (1999). The relationship between total quality management practices and operational performance. Journal of Operations Management, 17(4), 393-409.

Swanson, L. (2001). Linking maintenance strategies to performance. International Journal of Production Economics, 70(3), 237-244.

Saraph, J.V., Benson, P.G. and Schroeder, R.G. (1989). An instrument for measuring the critical factors of quality management. Decision Science, 20(4), 810-829.

Schonberger, R. (1982). Japanese Manufacturing Techniques. Free Press: New York.

Schonberger, R. (1986). World class manufacturing. The Lessons of Simplicity Applied. Free Press: London.

Schroeder, R. and Flynn, B.B. (2001). High performance manufacturing. John Wiley and Sons: New York.

Shah, R. and Ward, P.T. (2003). Lean manufacturing: context, practice bundles, and performance. Journal of Operations Management, 21, 129–149.

Sila, I. and Ebrahimpour, M. (2005). Critical linkages among TQM factors and business results. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 25(11), 1123-1155.

Sim, K. L. (2001). An empirical examination of successive incremental improvement techniques and investment in manufacturing technology. International Journal of Operations Production Management, 21(3), 373-399.

Swink, M., Narasimhan, R. and Kim, S.W. (2005). Manufacturing practices and strategy validation of a measurement instrument for studying supply chain management practices. Journal of Operations Management, 23(6), 618–641.

Ward, P. and Zhou, H. (2006). Impact of information technology integration and lean/ just-in-time practices on lead-time performance. Decision Sciences, 37(2), 177–203.

Yeung, A.C.L, Edwin-Cheng, T.C. and Lai, K. (2006). An Operational and Institutional Perspective on Total Quality Management. Production and Operations Management, 15(1), 156-170.

ANNEX 1

Indicators ofAdvanced Production Practice implementation.

Total Quality Management (TQM)

Constructs | Item description | Factor loading |

Customer Involvement

| We frequently are in close contact with our customers | 0.927 |

Our customers give us feedback on our quality and delivery performance. | 0.845 | |

Our customers are actively involved in our product design process | 0.715 | |

We regularly survey our customers’ needs. | 0.925 | |

Supplier Quality Involvement

| We strive to establish long-term relationships with suppliers. | 0.925 |

Our suppliers are actively involved in our new product development process. | 0.817 | |

We maintain close communication with suppliers about quality considerations and design changes. | 0.758 | |

We actively engage suppliers in our quality improvement efforts | 0.769 | |

Process Emphasis | We believe that the process, rather than the people performing the process, is the source of most errors. | 0.810 |

In our view, most problems result from the production system, rather than from individual employees. | 0.905 | |

In our view, the process is the entity that should be managed. | 0.689 | |

Non-financial indicators | On time delivery performance | 0.748 |

Flexibility to change product mix | 0.806 | |

Flexibility to change volume | 0.808 |

Just in Time/Lean Manufacturing (JIT/LM)

JIT Delivery by Suppliers | Our suppliers deliver to us on a just-in-time basis. | 0.696 |

We receive daily shipments from most suppliers | 0.668 | |

Suppliers frequently deliver materials to us. | 0.900 | |

Kanban | We use a kanban pull system for production control. | 0.946 |

We use kanban squares, containers or signals for production control. | 0.933 | |

Suppliers fill our kanban containers, rather than filling purchase orders. | 0.838 | |

Equipment Layout | The layout of our shop floor facilitates low inventories and fast throughput. | 0.689 |

Our processes are located close together, so that material handling and part storage are minimized. | 0.809 | |

We have located our machines to support JIT production flow. | 0.868 | |

We have laid out the shop floor so that processes and machines are in close proximity to each other. | 0.837 | |

Non-financial indicators | On time delivery performance | 0.625 |

Flexibility to change product mix | 0.847 | |

Flexibility to change volume | 0.8357 |

Total Productive Maintenance (TPM)

Autonomous Maintenance | Cleaning of equipment by operators is critical to its performance. | 0.764 |

Basic cleaning and lubrication of equipment is done by operators. | 0.959 | |

Operators inspect and monitor the performance of their own equipment. | 0.929 | |

Preventive Maintenance | We upgrade inferior equipment, in order to prevent equipment problems. | 0.668 |

In order to improve equipment performance, we sometimes redesign equipment. | 0.692 | |

We use equipment diagnostic techniques to predict equipment lifespan. | 0.752 | |

We do not conduct technical analysis of major breakdowns. | 0.767 | |

Maintenance Support | Our production scheduling systems incorporate planned maintenance. | 0.833 |

Equipment performance is tracked by our information systems. | 0.699 | |

Our systems capture information about equipment failure. | 0.746 | |

Non-financial indicators | On time delivery performance | 0.855 |

Flexibility to change product mix | 0.764 | |

Flexibility to change volume | 0.726 |